The 8-mile Kāneʻohe Bay on the island of Oahu teams with life and activity year round. A refuge to native wildlife, the Bay is also home to regional stakeholders such as the Marine Corps Base Hawaii, the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology Shark Research Lab (SharkLab) – and seven Starbucks in as many miles.

Locals and tourists flock to the area to take advantage of the peaceful, glasslike waters, sheltered from waves and swells by a vibrant coral reef. Snorkelers, kayakers, and local fishers may catch a glimpse of painted Surgeonfish, Hawaiian Green Sea Turtles, or Moray Eels that gather in the Bay. Wrapped protectively along the Ko’olu Mountain range, Kāneʻohe Bay sets a divine backdrop in Hollywood film favorites, such as Pearl Harbor and 50 First Dates.

At the risk of sounding like a travel blog, Kāneʻohe Bay is a definite hot spot on Oahu. Did you know the Bay was also a nursery for a critically endangered species – the Scalloped Hammerhead Shark?

Why Are Scalloped Hammerheads Critically Endangered? Efforts to protect endangered species are only effective when scientists and policymakers have the right data. Scalloped Hammerheads live about 30 years. In that time, they navigate low birth rates and limited or degraded nursery habitats in the Central Pacific.

Shark fin fishing poses a targeted risk to species survival, as Scalloped Hammerhead fins are highly prized on the global market. Meanwhile, local recreational or commercial fishers pose a bycatch (accidental) mortality risk. This is because these sharks have hammer-shaped heads that can easily get caught in nets, such as gillnets or longlines. Together, these hazards have contributed to a worrying population decline in recent decades.

Unfortunately, we have a limited knowledge of Scalloped Hammerhead behavior and habitat preference. If scientists knew more about movement patterns and feeding behavior, policymakers could enact seasonal protections to limit bycatch or similar risks. Better information could be crucial to protecting these sharks from further harm. That is why, when the SharkLab noted Scalloped Hammerhead pups in Kāneʻohe Bay, they jumped at the chance to learn.

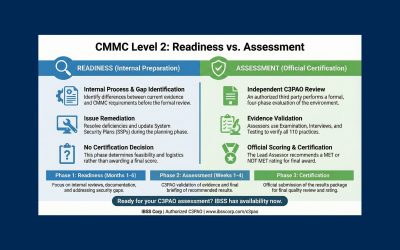

Tell Me More About This Study. Between 2009 and 2020, researchers and volunteers (led by Dr. Melanie Hutchinson from the SharkLab), captured, tagged, and analyzed data about Scalloped Hammerheads in the Bay. After IBSS won a shark tagging contract with the Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center in 2021, we joined this 10-year effort to study the species. IBSS helped to take this data, analyze it, and prepare it for publication. You can read about the final published research in the September 2023, edition of the Endangered Species Research (ESR Vol 52).

How Do You Study Shark Behaviors in the Wild? Scientists relied on fish tagging to capture biological and behavioral data that could be used to inform future protections and policies. Scalloped Hammerheads are very sensitive to human interaction, so scientists only tagged sharks that were at least 3 feet long. The researchers also limited the number of sharks they tagged by fishing only between May and September. They tagged three to four sharks every year over 10 years. They used two types of tags to capture different kinds of data.

- Acoustic Telemetry Tags. These tags capture high resolution location data (think GPS), but only transmit data when a shark is within 500 meters of a receiver. The SharkLab placed 237 receivers along the Hawaiian Archipelago, many around Kāneʻohe Bay. Divers manually collected this data every 6-9 months, so receivers had to remain accessible in shallow water. These tags can last up to 10 years and cost about $700 per shark. These features make them an excellent tool to study movements in the Bay or near surface water.

- Satellite Telemetry Tags. Satellite based tags give scientists a broader view of movement behaviors because they do not rely on proximity to a receiver. These tags collect position data, and information related to body temperature and depth. They remain attached to sharks for a specific amount of time – often 365 days – and transmit data to overhead satellites when they pop off the shark. Because this tool offers a wider range of data capabilities, it comes with a higher ticket price ($4,000/shark). Scientists used these tags to gather information about Scalloped Hammerhead deep diving behavior, which many believe is connected to shark feeding and biorhythm. Knowing more about how and why Scalloped Hammerheads deep dive could be critical to future protective policies.

What Did You Find Out? This was the first study able to document adult male and juvenile sharks’ wide ranging movement patterns and habitat preferences. This study revealed that:

- There is a robust population of Scalloped Hammerheads in Kāneʻohe Bay. This means the Bay is a critical location to focus conservation efforts. Protecting pups from hazards like gillnets during nesting (May through September) could help to reduce mortality rates.

- These sharks are likely regionally distinct. Sharks tagged in the Bay seemed to move only along the Northwest and Main Hawaiian Islands. Fifty percent of sharks returned to the Bay during nesting season. This means they have high “site fidelity” – reinforcing the idea that the Bay is a critical zone for conservation. Although this needs to be tested further, the research suggests these sharks may be genetically separate from other Scalloped Hammerheads. If true, conservation efforts may become even more crucial.

- Males and females behave differently during nesting season. Over the 10-year study, the researchers never caught an adult female. This surprised scientists, as the Bay is known as an important nursery. Other studies recorded 180-660 females in the Bay during nesting. The absence of adult females in this study suggests a potential “sexual segregation” between males and females. If true, conservation efforts must adjust to these behavioral differences.

- Hammerhead Sharks can hold their breath during deep dives. Ok, if you attend your local trivia nights, you might already know that hammerheads can “hold their breath” by closing their gills during deep dives. However, this 10-year study only recorded deep diving at night, which intrigued scientists. About 85% of the time, Scalloped Hammerheads swim within 300 feet of the surface. Scientists do not know what causes them to deep dive, but believe it may be to find food. Other studies that looked at hammerhead shark stomach contents noted remains from mesopelagic fish and other prey like squid. These species can often only be found between 200-1,000 meters below sea level and on the seafloor.

Why Does This Research Matter and What Happens Next? This research project opened new questions for scientists studying Scalloped Hammerhead, and for conservation policymakers. Molly Scott, Ph.D., is the corresponding author for this 10-year study. After the research was published in the journal, Endangered Species Research, Dr. Scott sent the publication to Hawaii fisheries managers such as the State of Hawaii Division of Aquatic Resources. Implementing policy is a slow process that must take into account the complex factors of life in Kāneʻohe Bay. Dr. Scott will continue to share this research with policymakers and the public.

Acknowledgments. IBSS recognizes Dr. Hutchinson, and the SharkLab researchers, volunteers and organizational contributors who have supported this research since 2009. IBSS thanks Dr. Scott for interviewing with us about this exciting research in the Central Pacific. We are honored to be part of this mission and to promote this ongoing work to the public.